The Iliad, one of the cornerstones of Western literature, isn’t merely a tale of war and heroism; it’s also contains a myriad of powerful myths and legends. Homer weaves these ancient stories into his epic, bringing moral complexity and thematic richness to the world of Greek warriors and gods. To start this series off, I will focus on these three myths in particular: the Wrath of Achilles, the Myth of Niobe, and the Shield of Achilles. Each adds depth, reflecting on human nature, fate, and the consequences of pride. Let’s explore these myths in detail and analyse their broader implications in The Iliad!

Achilles’ anger is not only a driving force in The Iliad but also one of its most profound thematic explorations. From the very opening line, “Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles,” Homer signals that Achilles’ wrath will shape the entire story; this anger is not simple or fleeting—it is complex, multifaceted, and transformative, affecting both Achilles himself and the entire Greek army.

The initial cause of Achilles’ anger lies in a conflict with Agamemnon, the Greek commander. Agamemnon and Achilles, though fighting on the same side against the Trojans, clash over their status, pride, and honor. In Book 1, Agamemnon is forced to return his war prize, a woman named Chryseis, to her father, a priest of Apollo, to end a plague sent by the god in response to the priest’s prayers. Agamemnon, furious at losing Chryseis, demands compensation and decides to take Achilles’ war prize, Briseis, as a replacement.

In the world of The Iliad and Ancient Greece, war prizes symbolize honour and status. They are tangible markers of a warrior’s glory and accomplishments. By claiming Briseis, Agamemnon publicly dishonours Achilles, undermining his status among the Greeks. This act wounds Achilles’ pride deeply, not just as a personal offense but as a direct assault on his honour, reputation, and place in Greek society. Achilles’ anger, therefore, stems from more than jealousy or frustration; it’s a response to a violation of his heroic identity and a complete disrespect of his Timé.

Achilles is faced with a choice: to submit to Agamemnon’s authority or to assert his own honour by withdrawing from the war. He chooses the latter, retreating to his tent and refusing to fight, even though he knows his absence will weaken the Greek forces. This decision is both personal and symbolic, as it shows that Achilles values his honour more than the Greek cause. His choice to abstain from battle out of wounded pride reflects the individualistic nature of heroism in Homer’s time, where personal honour often eclipses duty to the collective.

Achilles’ anger represents hubris, the excessive pride that can lead to personal downfall. Yet, it’s more complex than mere arrogance. Achilles feels justified in his anger because he believes that he, not Agamemnon, has earned the right to command respect. He is the greatest Greek warrior, essential to their victory, and his achievements should grant him a higher status than even the Greek commander. However, by taking Briseis, Agamemnon reduces Achilles to the level of any ordinary soldier, challenging Achilles’ understanding of himself and his place in the world.

Achilles’ anger also challenges the Greek heroic code, where warriors are expected to serve the collective good. His decision to withdraw exposes the limitations of a value system based on individual glory. By putting his pride before the Greeks’ success, Achilles places himself above his comrades, even though they depend on his strength. This choice to prioritize honour over duty sets the stage for a broader conflict within Achilles himself, as he wrestles with his own values, identity, and sense of purpose.

As the story unfolds, Achilles’ anger has devastating effects. Without him, the Greeks suffer severe losses against the Trojans. Eventually, Achilles’ closest friend, Patroclus, dons Achilles’ armour to rally the Greek troops and inspire hope. However, Patroclus is killed in battle by Hector, the Trojan prince, leading Achilles to confront the tragic consequences of his rage. The death of Patroclus brings Achilles to a moment of reckoning, transforming his anger into a desire for revenge against Hector, and ultimately leading him back to the battlefield.

This transformation in Achilles’ anger—from wounded pride to vengeful fury—marks a turning point in the narrative. His grief over Patroclus’ death softens his pride, shifting his focus from personal honor to justice for his friend. This shift suggests that Achilles is not a one-dimensional character defined only by wrath; he is capable of deep loyalty and emotional complexity. His return to battle is both an act of vengeance and a tribute to Patroclus, showing that Achilles can transcend his pride for the sake of love and loyalty.

The story of Niobe appears in The Iliad in Book 24, serving as a strong example of pride, grief, and humility. In the context of the epic, Niobe’s myth is not recounted in full detail, but its essence is used to emphasize the theme of excessive pride, or hubris (like Achilles), and to reflect on the nature of mourning. The story is mentioned when Priam, the king of Troy, grieves the death of his son Hector, who has been slain by Achilles. In this moment of profound sorrow, Priam draws on Niobe’s tale as a way to understand and moderate his grief, seeking solace in the face of his overwhelming loss.

The myth of Niobe originates in ancient Greek tradition. Niobe, a mortal queen, was the daughter of Tantalus, a figure who himself embodied hubris through his defiance of the gods. Niobe, known for her beauty and noble lineage, married Amphion, king of Thebes, and together they had many children. In some versions of the myth, Niobe boasts of her twelve children (six sons and six daughters), while others describe her as having fourteen. Regardless of the exact number, Niobe’s large family is a point of pride for her—one that ultimately leads to her downfall.

Niobe’s pride becomes excessive when she compares herself to the goddess Leto, mother of the divine twins Apollo and Artemis. In a moment of arrogance, Niobe claims superiority over Leto, mocking her for having only two children. This act of pride—believing herself greater than a goddess because of her numerous offspring—represents the ultimate hubris, an affront to the gods. Leto, deeply insulted, calls upon her children to punish Niobe for her arrogance. Apollo and Artemis heed their mother’s plea and exact vengeance on Niobe by killing all her children, one by one, with their arrows. Niobe, once so proud of her children, is left desolate, watching as her pride turns to unbearable sorrow.

As Niobe weeps over her loss, her grief becomes endless, consuming her entirely. In some versions of the myth, the gods transform her into stone, her tears flowing eternally as a river. This image of Niobe as a weeping stone is a haunting reminder of the consequences of hubris and the inescapable pain that often follows excessive pride. Niobe’s story illustrates the Greek moral that mortals should always remember their place relative to the gods, who can just as easily grant blessings as they can take them away.

In The Iliad, Priam recalls Niobe’s story as he seeks to cope with his own grief. His beloved son Hector, the champion of Troy and a source of great pride, has been slain and dishonoured by Achilles, who initially refuses to return Hector’s body for proper burial. Priam, though devastated, draws strength from Niobe’s example, recognizing that even in the face of profound loss, life must continue. Niobe’s myth, therefore, serves as a reflection on the necessity of moving forward, even when grief seems insurmountable.

By referencing Niobe, Priam acknowledges a universal truth about grief: while loss is inevitable, it cannot consume one’s life entirely. Although Niobe’s sorrow is eternal, her tale is invoked as a reminder that mourning must eventually give way to endurance and resilience. This perspective helps Priam gather the courage to seek out Achilles and request the return of Hector’s body. Priam’s understanding of Niobe’s grief allows him to confront Achilles, showing that his love for his son, while immense, does not have to end in endless mourning. Instead, he can honour Hector’s memory by ensuring that he receives the proper rites, securing his place in the afterlife according to Greek custom.

Moreover, Niobe’s myth serves as a powerful warning against hubris. Priam, unlike Niobe, understands the importance of humility. Although he is a king, Priam knows that he is a mortal, and he does not elevate himself above others or challenge the gods. In fact, Priam approaches Achilles with humility, bearing gifts and imploring Achilles to respect the bond between father and son. Priam’s humility contrasts sharply with Niobe’s pride, suggesting that while grief may be inevitable, suffering can be mitigated by approaching life with humility and acceptance.

The myth also underscores the Greek belief in the gods’ role as enforcers of cosmic order. Niobe’s tragedy reminds mortals that pride and arrogance carry severe consequences. By invoking Niobe’s story, Homer reinforces the notion that balance and humility are essential virtues. The gods, as seen in Niobe’s punishment, act as arbiters of justice, maintaining a moral order by punishing hubris. For Priam, this serves as a lesson: he understands that defying the will of the gods or acting out of pride will only bring more suffering upon himself and his kingdom.

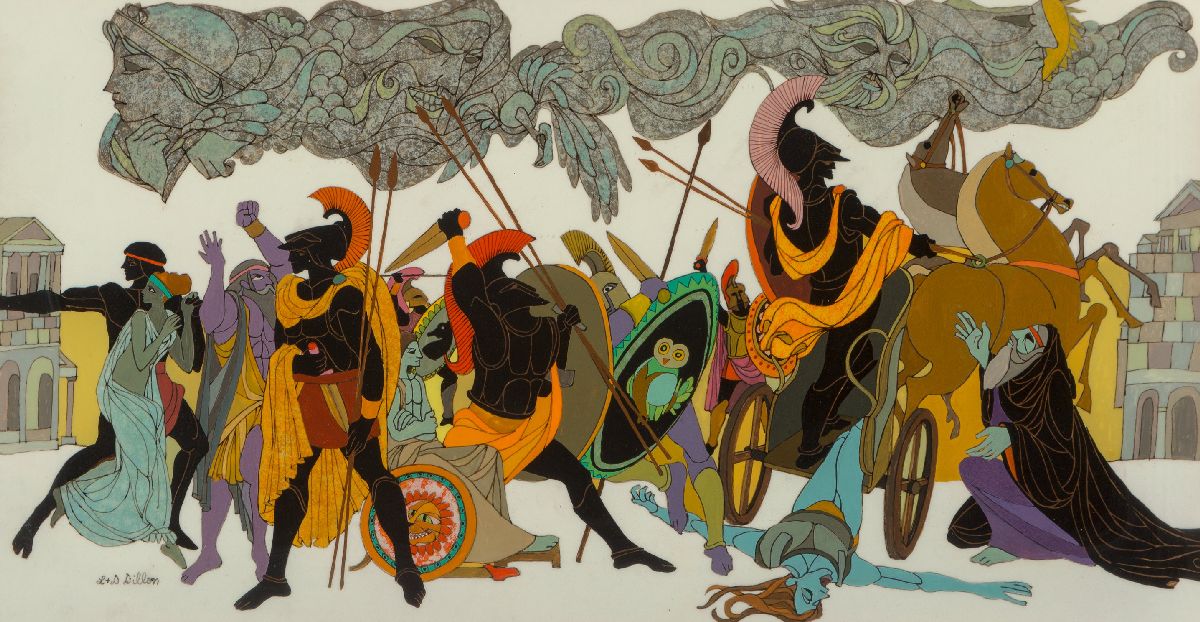

The Shield of Achilles is one of the most powerful symbols in The Iliad, serving as a microcosm of the human experience and a meditation on the dualities of life. This remarkable object is forged by Hephaestus, the god of blacksmithing, in Book 18. After the death of Patroclus, Achilles decides to return to battle to avenge his friend, knowing that he faces near-certain death as a result. Achilles’ mother, Thetis, commissions Hephaestus to forge a new set of armor for her son, and the shield becomes a masterpiece, depicting scenes that capture the entirety of human existence.

The shield is unique in The Iliad not only for its craftsmanship but for the symbolic weight it carries. While The Iliad largely focuses on the devastation of war, the shield presents a more balanced perspective. It displays both the beauty and the brutality of life, portraying scenes of war alongside those of peace, joy, and harmony. The images on the shield reveal the complexities of the world Achilles fights for, contrasting the horrors of the Trojan War with the fullness of life that exists beyond the battlefield.

Hephaestus forges the shield with several intricate layers, depicting various scenes from human life. At its centre lies an image of the earth, the sea, and the heavens, symbolizing the cosmos and the broader forces that govern existence. Surrounding this core, Hephaestus includes scenes of human civilization, such as a bustling city at peace and another city embroiled in war.

In the peaceful city, people are engaged in weddings, celebrations, and legal disputes. Here, the shield reflects the vibrant social life that continues despite conflict elsewhere, capturing the rhythms of community, justice, and celebration. The city at peace stands as a stark contrast to the city at war, where warriors clash, ambushes are planned, and violence threatens to consume everyday life. This juxtaposition of peace and war on the shield underscores the dual nature of human society: it is both nurturing and destructive, driven by both harmony and conflict.

The shield also depicts scenes of agricultural life, with farmers plowing fields, harvesting crops, and tending to animals. These images of rural life illustrate the cyclical, life-sustaining activities that support human civilization. The presence of these peaceful, productive scenes serves as a reminder of what is at stake in the war—a life where people live, grow, and create. It emphasizes that human life encompasses far more than the violence Achilles experiences on the battlefield, adding depth to his understanding of what he is fighting to protect.

The shield of Achilles serves as a symbol of the world beyond Achilles’ immediate concerns. Throughout the poem, Achilles is focused on honour, vengeance, and his individual legacy, often at the expense of seeing the larger picture. The shield’s imagery, however, presents him with a vision of a world that exists outside of his personal quest for glory. By portraying scenes of both peace and war, Hephaestus creates a balanced view of existence, one that acknowledges life’s pleasures as well as its pains, life’s beauty alongside its brutality.

In a sense, the shield represents the very world Achilles is choosing to leave behind as he prepares to return to battle. When Achilles gazes upon the shield, he is confronted with a vision of human life in its entirety, not just the violent, honor-driven aspect that he embodies. The shield reminds him that life contains elements of joy, community, and continuity, contrasting with the warrior’s life of isolation and violence. In this way, the shield becomes an object of introspection, urging Achilles to consider the broader implications of his actions.

The imagery on the shield also serves as a reminder of fate and inevitability. Just as Achilles’ life will be cut short due to his choice to avenge Patroclus, the shield reflects the inevitability of life’s cycle—birth, death, creation, and destruction. It serves as a microcosm of the world Achilles is about to re-enter, one that is governed by the same forces of mortality and fate that rule over him. In the face of these images, Achilles’ sense of honor and glory takes on a new significance: he is part of a larger order, one that transcends individual heroism.

Another layer of symbolism lies in the fact that the shield is a creation of the god Hephaestus. Hephaestus, as a divine craftsman, imbues the shield with a sense of artistry and creativity that contrasts with the destruction of war. The shield is not merely functional armor but a masterpiece that represents the pinnacle of divine craftsmanship. In a world so focused on the act of killing, Hephaestus’ creation stands as a testament to the creative power of the gods, a reminder that even in the context of war, beauty and order exist.

In this way, the Shield of Achilles transcends its role as a piece of armour. It becomes a reflection on the nature of human life, an exploration of the world’s dualities, and a meditation on the limits and sacrifices of heroism. The shield encapsulates the tragic beauty of The Iliad, offering a glimpse of the life Achilles will never fully know as he chooses to walk the path of honour and revenge. The shield also serves as a bridge between the mortal and the divine. As a god-made object, it imbues Achilles with a form of divine protection, even as he faces mortal peril. It suggests that Achilles, while mortal, has been granted a unique place within the cosmic order, symbolized by this godly gift. Yet, even with this divine armour, Achilles remains vulnerable to the fates that govern all mortals. This emphasizes the Greek belief that while mortals can achieve greatness, they remain subject to the ultimate authority of fate and the gods.

Each myth woven into The Iliad contributes to a deeper understanding of Homer’s world, where gods and humans alike grapple with pride, grief, fate, and honor. The Wrath of Achilles illustrates the destructive power of unchecked pride, while the Myth of Niobe serves as a cautionary tale against excessive pride and mourning. And finally, The Shield of Achilles symbolizes life’s complexity, reflecting both the beauty and horror of the world. By examining these myths, I hope I am able to give you a deeper appreciation of The Iliad as not only an epic of war but also a profound meditation on life’s enduring struggles and lessons.

The Chain Reaction of Us

our story is made of chain reactions – we are just the sum of tiny miracles pretending to be[…]

FIGuring Life Out

Looking at Sylvia Plath’s Fig Tree: On Choice, Possibility, and Growing Into Who We Are I turned eighteen recently,[…]

The F-Word We’re Afraid To Say

WHY ARE WE SO SCARED OF THE WORD “FEMINIST”? There’s a strange, bitter irony in the fact that a[…]

No responses yet