“Kantian ethics is a helpful method of moral decision making. discuss.”

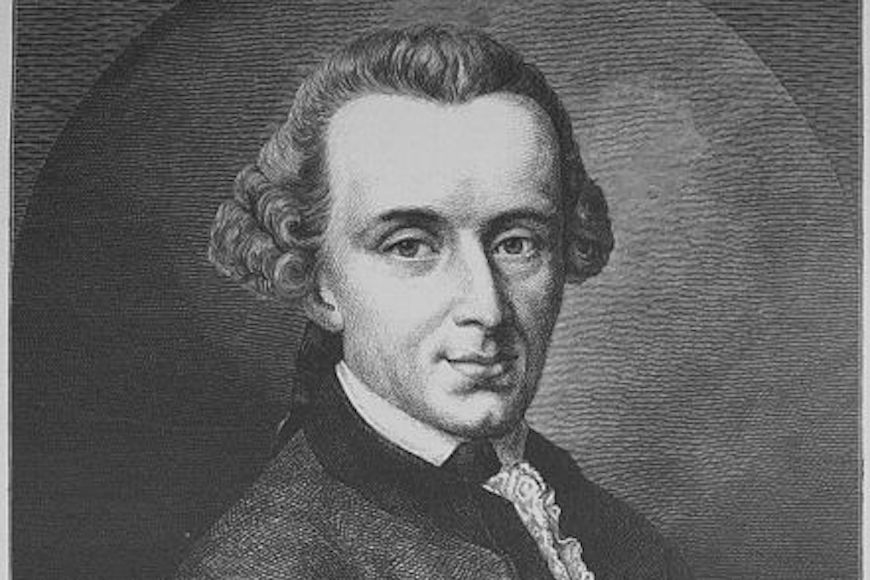

Kantian ethics, developed by Immanuel Kant, provides a deontological framework for moral decision-making centred on duty, reason, and respect for human dignity. It maintains that moral actions arise from a good will—acting in accordance with duty for its own sake—and offers an objective, universal moral law. Despite criticisms of its rigidity and abstraction, this essay will argue that Kantian ethics is a helpful method for moral decision-making because it provides a rational, consistent, and principled approach that prioritizes the intrinsic value of individuals. Through analysis of Kant’s key principles, the categorical imperative, and the postulates of practical reason, I will demonstrate how Kantian ethics offers a robust framework for navigating moral challenges.

At the heart of Kantian ethics is the idea that the only thing that can be called “good without qualification” is a good will. Kant argues that moral worth does not depend on the consequences of an action but on the purity of motive behind it. Actions are moral if performed out of duty, guided by reason, and not influenced by emotions or self-interest. For example, saving a drowning person for the sake of a reward or praise lacks moral value because it is not motivated by duty. As Kant writes, “An action done from duty has moral worth.”

Critics, such as Bernard Williams, argue that Kantian ethics neglects the moral importance of emotions, such as compassion or love, which are often central to human moral experience. Williams contends that moral actions motivated by feelings can still be virtuous and suggests that Kant’s rejection of emotions reduces the richness of ethical life. However, this critique misunderstands the role of emotions in Kantian ethics. Kant does not deny the value of emotions but insists that they cannot form the foundation of morality because they are subjective and inconsistent. By grounding morality in reason and duty, Kantian ethics ensures universal applicability and- as evidenced by Macintyre’s – provides a “counterbalance [to] the moral relativism that emotion-based ethics often invites”.

In my view, one supported by the aforementioned critics, this emphasis on duty and reason demonstrates the strength of Kantian ethics. While, emotions can inspire moral actions, they are unreliable as a universal guide to right and wrong. Essentially, Kant’s framework provides clarity and consistency, offering individuals a stable moral compass even when emotions might cloud judgment. For me, this makes Kantian ethics a uniquely helpful approach to moral decision-making.

A fundamental distinction in Kantian ethics lies between hypothetical and categorical imperatives, which describe two different kinds of moral commands. Hypothetical imperatives are conditional, dependent on personal desires or outcomes, and framed as “if-then” statements. For example, a hypothetical imperative might state: “If you want to make someone happy, you should tell the truth.” These commands are practical and subjective, varying based on the goals or circumstances of the individual. Kant, however, criticizes hypothetical imperatives for their lack of moral value, as they are contingent on external factors rather than grounded in universal, dutiful principles.

In contrast, categorical imperatives are unconditional and absolute, applying to all rational beings regardless of personal desires or specific situations. They are commands of reason that dictate what one ought to do purely out of duty and good will. For Kant, morality is rooted in these categorical imperatives because they provide a framework for evaluating actions based on their universality and inherent moral worth. One of Kant’s categorical imperatives is the prohibition of lying, which he argues cannot be universalized without contradiction: if everyone lied, the concept of truth-telling would be undermined, making communication impossible. This highlights the objectivity and consistency of categorical imperatives as a guide for moral action. Unlike hypothetical imperatives, categorical imperatives are not concerned with the consequences of an action but with the principle underlying it, making them central to Kant’s moral philosophy.

The categorical imperative is the stand out of Kantian ethics, and its evaluation reveals both its strengths and weaknesses in practical application. The first formulation—the formula of the universal law of nature—requires individuals to act only according to maxims they could will to become universal laws. This principle establishes a rational test for determining whether an action is morally permissible. For example, Kant argues that lying fails this test because if everyone lied, the concept of truth-telling would collapse, leading to a contradiction in the very act of communication. This logic provides a clear, objective basis for evaluating actions, avoiding the subjective variability of hypothetical imperatives.

However, critics such as Philippa Foot argue that this rigidity oversimplifies moral decision-making. They suggest that some actions, like lying, may be morally justified in certain contexts, such as lying to protect someone from harm. Foot challenges the inflexibility of Kant’s approach, claiming that morality cannot always adhere to strict universal laws. Another common criticism is that it is impossible to get everyone to act according to universal rules. Human beings often fail to live up to moral ideals due to self-interest, emotional impulses, or situational pressures. However, this reflects a human error rather than a flaw in Kant’s ethical theory. Kant’s system is not predicated on the assumption that all people will perfectly follow moral laws but instead provides an aspirational standard for rational beings to strive toward. As Roger Scruton observes, “The failure to act morally reflects human weakness, not a defect in the moral law itself.”

To further diminish these critiques, Kant’s defenders argue that his prohibition on lying preserves trust and moral integrity in society. As Scruton once again observes, “The universality of the categorical imperative ensures that morality remains principled rather than pragmatic.” While individual cases may seem to justify lying, such exceptions undermine the moral fabric of society over time.

Another strength of the categorical imperative lies directly in its universality, which ensures moral consistency across different cultures and contexts. Unlike ethical relativism, which allows moral principles to vary, Kant’s approach offers an absolutist standard that applies to all rational beings. This universal applicability is a key reason why Kantian ethics remains relevant. However, critics argue that not all maxims can realistically be universalized. For instance, Sartre’s example of conflicting duties—such as a student torn between caring for his mother and fighting for justice—highlights how universal maxims can clash, leaving individuals without clear guidance.

In my view, this criticism is not entirely persuasive. Kant acknowledges the complexity of moral dilemmas and does not claim that universal laws eliminate all moral conflicts. Rather, the categorical imperative provides a rational framework for individuals to navigate these conflicts. For me, the formula of the universal law of nature is particularly helpful because it encourages individuals to consider the broader implications of their actions.

The second formulation—the formula of the end in itself—requires that individuals always treat humanity, whether in their own person or in the person of another, as an end and never merely as a means. This maxim safeguards the intrinsic dignity and worth of all human beings, rooted in their ability to make free and rational choices. By emphasizing that people must not be exploited or dehumanized, Kant establishes a moral principle that protects individuals from being used for ulterior motives, such as manipulation for financial or personal gain. Christine Korsgaard praises this maxim, noting that “Kant’s ethics uniquely upholds the value of human beings as autonomous moral agents, rather than mere instruments for achieving external ends.” Unlike utilitarianism, which may justify using individuals as tools for the greater good, Kantian ethics insists on respect for each person’s autonomy and humanity.

However, some critics argue that Kant’s emphasis on rationality as the basis for moral worth is problematic. Louis Pojman raises the concern that if rationality is the source of intrinsic value, then those with greater rational capacity might be considered more valuable than those with less, such as children or individuals with cognitive impairments. Moreover, Kant’s own racist and sexist writings, which suggested the inferiority of non-European peoples and women, seem to contradict the principle of universal human dignity. As Pojman, Mill, and other scholars have noted, this contradiction raises concerns about whether Kant consistently upheld his ethical framework.

In response, defenders like John Rawls argue that Kant’s ethical theory must be distinguished from his personal prejudices. While Kant’s writings on race and gender are undeniably problematic, they are not part of his ethical theory but rather historical biases that reflect the flawed context of his time. As Allen Wood explains, “Kant is best seen as an inconsistent egalitarian rather than a consistent inegalitarian.” This means that Kant’s ethical principles, such as the intrinsic worth of all humans, ultimately undermine his own prejudices rather than being undermined by them.

Personally, this defense is persuasive. Kant’s ethical framework, particularly the formula of the end in itself, is inherently egalitarian and does not rely on his personal biases. While his racism and sexism are reprehensible, they do not invalidate the moral value of treating humanity as an end in itself. As I see it, this principle is one of the most profound aspects of Kantian ethics, as it provides a foundation for universal respect and equality, even if Kant himself occasionally failed to live up to it. By separating his theory from his prejudices, we can appreciate the relevance and humanity of this maxim in protecting individual dignity across all contexts.

The third formulation—the formula of the kingdom of ends—adds a communal element to Kantian ethics by envisioning a society where individuals act as if they were lawmakers in a universal moral kingdom. This principle inspires individuals to consider the collective impact of their actions, promoting a sense of moral responsibility toward others. However, critics like Sartre argue that this maxim is too abstract and fails to provide practical guidance for resolving real-world dilemmas. For instance, in situations of conflicting duties as mentioned previously, such as choosing between personal loyalty and justice, the kingdom of ends does not offer concrete solutions.

Despite these challenges, I believe the kingdom of ends remains a valuable moral ideal. While it may not resolve every conflict, it encourages individuals to think beyond self-interest and consider the broader implications of their actions. Ultimately, this principle highlights the connection between morality and the importance of acting with integrity and compassion in a complex world.

Overall, the categorical imperatives provide a principled and universal approach to moral decision-making, despite criticisms of their rigidity and abstraction. By emphasizing duty, reason, and respect for human dignity, they offer a strict framework for navigating ethical challenges. For me, the strengths of the categorical imperatives far outweigh their limitations, as they provide clarity and consistency in a world often fraught with moral ambiguity.

Kantian ethics is further supported by its metaphysical postulates, particularly the belief in human freedom, the existence of God, and immortality. These postulates are not empirical truths but necessary assumptions for moral reasoning. For instance, the postulate of freedom underpins moral responsibility, as individuals must have the ability to choose between right and wrong. Similarly, the postulate of God provides a basis for the ultimate reconciliation of morality and happiness, while the postulate of immortality allows for the pursuit of moral perfection.

Critics dismiss these postulates as speculative and unnecessary for ethical reasoning. However, Kant himself acknowledges their non-empirical nature, arguing that they are practical necessities rather than theoretical claims. As Stephen Palmquist explains, “Kant’s postulates serve as the scaffolding for his ethical system, enabling individuals to act morally without requiring empirical proof.” In my opinion, the postulates add depth and coherence to Kantian ethics. While they may not be essential for all moral reasoning, they offer a philosophical foundation that aids in developing Kant’s ethical framework. For me, the postulate of freedom is particularly compelling, as it affirms the autonomy and responsibility of moral agents, reinforcing the dignity of human beings as rational actors.

In conclusion, Kantian ethics is a highly helpful method of moral decision-making due to its emphasis on duty, universality, and respect for human dignity. While critics highlight its rigidity and occasional abstraction, these critiques often misunderstand or underestimate the value of its principles. By providing clear guidelines through the categorical imperative and its formulations, Kantian ethics ensures consistency, moral accountability, and the protection of individual dignity. For me, its commitment to acting morally for the sake of morality itself—regardless of consequences—makes it a uniquely principled and timeless ethical system. As Roger Scruton aptly summarizes, “Kantian ethics reminds us that morality is not a matter of personal preference or pragmatic calculation but a universal commitment to the good.” Thus, despite its supposed challenges, Kantian ethics remains a vital and practical framework for moral decision-making in both personal and societal contexts.

The Chain Reaction of Us

our story is made of chain reactions – we are just the sum of tiny miracles pretending to be[…]

FIGuring Life Out

Looking at Sylvia Plath’s Fig Tree: On Choice, Possibility, and Growing Into Who We Are I turned eighteen recently,[…]

The F-Word We’re Afraid To Say

WHY ARE WE SO SCARED OF THE WORD “FEMINIST”? There’s a strange, bitter irony in the fact that a[…]

No responses yet