“A word after a word after a word is power.”

This quote by Margaret Atwood, featured at the bottom of my blog, encapsulates the transformative force of storytelling. Stories are not merely entertainment; they are tools of influence, vessels of knowledge, and reflections of our collective humanity. From ancient myths passed down orally to the ground-breaking impact of the printing press, the history of literature is a testament to the enduring power of words.

This post will trace the journey of storytelling from its earliest roots in oral traditions to the revolutionary invention of the printing press. Along the way, we’ll explore how literature evolved from a communal experience to a more individual, immersive act, shaping cultures, societies, and the very way we think. Every step of this journey highlights Atwood’s assertion—words, in their various forms, have always been power.

Long before the written word existed, stories lived in the minds and on the tongues of storytellers. Oral literature was the lifeblood of ancient communities, used to preserve history, teach values, and entertain. In societies where writing was unknown or inaccessible, oral traditions ensured that cultural heritage was passed from one generation to the next.

The epics of Homer, The Iliad and The Odyssey, are prime examples of oral storytelling’s endurance. These tales were passed down by Greek rhapsodes or bards who recited them in poetic form, relying on rhythm, repetition, and mnemonic devices to ensure their accuracy. Similarly, the Norse skalds preserved the sagas of Viking heroes, and African griots served as living libraries, recounting histories and genealogies with astonishing precision.

Oral traditions were not limited to epic tales. Fables, riddles, proverbs, and songs formed part of this rich tapestry. For instance, Aesop’s fables, though written down later, originated as oral tales designed to convey moral lessons. Meanwhile, indigenous communities worldwide developed their own storytelling traditions, such as the Dreamtime stories of Australian Aboriginal cultures or the creation myths of Native American tribes.

Beyond their narrative power, oral traditions served as social rituals. Communities would gather to listen, their shared experience fostering unity and cultural identity. However, oral storytelling also had limitations. The accuracy of stories could waver with time, and their reach was confined to those who could hear them first-hand. This set the stage for a seismic shift in the way humanity recorded its stories: the advent of written literature.

The invention of writing transformed human communication. Around 3100 BCE, the Sumerians developed cuneiform,

Sumerian Cuneiform

one of the earliest writing systems, to record trade transactions. Soon, writing expanded beyond commerce to encompass history, law, and storytelling. Other early systems, like Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese oracle bone script, similarly gave permanence to ideas and narratives.

Handwritten manuscripts marked the beginning of literature as we know it. In ancient Mesopotamia, works like The Epic of Gilgamesh were inscribed onto clay tablets, providing a tangible record of human creativity. Manuscripts allowed stories to transcend the limitations of memory and geography, enabling them to reach distant lands and future generations.

By the time of the Classical civilizations of Greece and Rome, writing had become a central feature of literary production. Greek tragedies and comedies by playwrights such as Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes were written down, though they originated as performed works. Similarly, Roman authors like Virgil (The Aeneid) and Ovid (Metamorphoses) crafted texts designed for both oral recitation and private reading.

The rise of ancient libraries further underscores the importance of written literature. The Library of Alexandria, one of the ancient world’s greatest repositories of knowledge, housed manuscripts from across the Mediterranean, demonstrating the growing value of written texts. Similarly, Chinese emperors established extensive archives to preserve literary and administrative works, while Indian scholars inscribed sacred texts like the Vedas and Upanishads on palm leaves.

However, creating manuscripts was labour-intensive and expensive. Scribes painstakingly copied texts by hand, often working for years on a single book. Religious institutions were central to this process, with monasteries across Europe preserving and copying texts like the Bible. This exclusivity persisted until the arrival of a game-changing invention in the 15th century: the printing press.

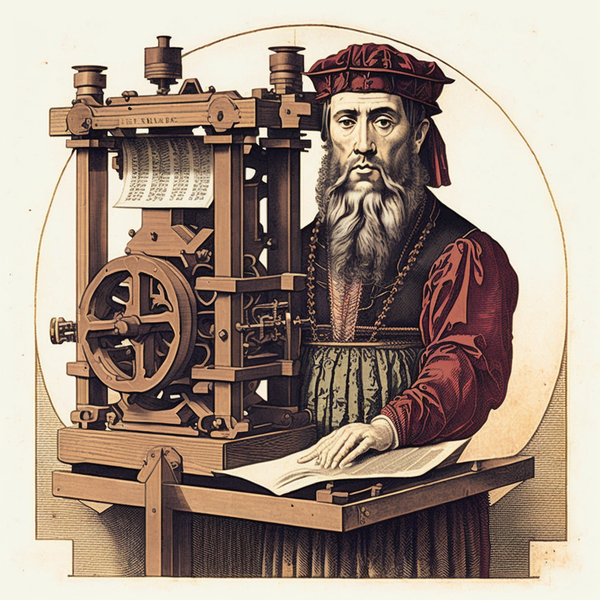

The printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg in 1440, revolutionized the way stories and knowledge were disseminated. For the first time in history, books could be mass-produced, dramatically reducing their cost and making them accessible to a broader audience.

Gutenberg’s innovation relied on movable type, which allowed individual letters to be rearranged and reused. The first major work printed using this method was the Gutenberg Bible, a beautifully crafted text that showcased the potential of the new technology. Over the next few decades, printing spread across Europe, transforming education, religion, and culture.

Before the printing press, books were rare treasures; after its invention, they became commodities. The press facilitated the rapid spread of ideas, fuelling movements like the Reformation and the Renaissance. Martin Luther’s writings, for instance, were printed and distributed widely, enabling his criticisms of the Catholic Church to reach audiences far beyond his immediate circle. Similarly, the dissemination of Renaissance texts helped revive Classical knowledge and inspire scientific discoveries.

The press also paved the way for the mass production of secular literature. Previously, literature was largely religious or philosophical in nature, but the printing press allowed for the creation and circulation of novels, plays, and poetry on an unprecedented scale.

Though storytelling had ancient roots, the novel as a distinct genre emerged much later. Early works like The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (11th century Japan) and The Golden Ass by Apuleius (2nd century Rome) are often regarded as precursors to the modern novel. These narratives were long, intricate, and focused on individual characters, setting the stage for what the novel would become.

The printing press made novels widely available, leading to their rise in popularity. Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote, published in two parts in 1605 and 1615, is often considered the first modern novel. It was not only a satire of medieval chivalry but also a reflection on storytelling itself, embodying the shift from oral tradition to written narrative.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw an explosion of novel-writing, with authors like Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, and the Brontë sisters reaching audiences across class divides. The novel offered a new kind of literary experience: private, immersive, and often deeply personal. Readers could engage with characters’ inner lives and explore fictional worlds, expanding the boundaries of their imagination.

The printing press did more than produce books; it fundamentally changed the relationship between people and stories. Previously, storytelling had been a communal activity, shared aloud in public spaces. With the advent of printed literature, reading became an individual, often solitary pursuit.

The spread of printed texts also democratized knowledge. Literacy rates began to rise as books became more affordable, and education expanded beyond the elite. The printing press was instrumental in disseminating the ideas of the Enlightenment, which emphasized reason, science, and individual rights. Without it, the intellectual revolutions of the 17th and 18th centuries might never have occurred.

Genres like poetry, essays, and drama also flourished in the age of print, diversifying the literary landscape. Writers were no longer reliant on patronage; they could reach audiences directly, creating a new economy of ideas and artistry.

The printing revolution also laid the groundwork for modern publishing. By the 20th century, literature was accessible in multiple forms, from serialized novels in newspapers to mass-market paperbacks. This accessibility further bridged the gap between oral and written traditions, ensuring that stories could reach audiences of all backgrounds.

The journey of literature from oral traditions to printed texts is one of humanity’s most transformative stories. Each stage—oral storytelling, handwritten manuscripts, and the printing revolution—has shaped how we understand ourselves and our world.

Today, we live in an era of unprecedented access to literature. Digital platforms, audiobooks, and e-readers bring stories to our fingertips, continuing the legacy of democratization begun by the printing press. Yet, the origins of literature remind us of the enduring power of storytelling to connect us, whether through the spoken word or the printed page.

As you pick up your next book or listen to a story, take a moment to reflect on the incredible journey that brought it to you. In every word lies the echo of ancient storytellers, the meticulous labour of scribes, and the ingenuity of printers who believed that stories deserved to be shared with the world.

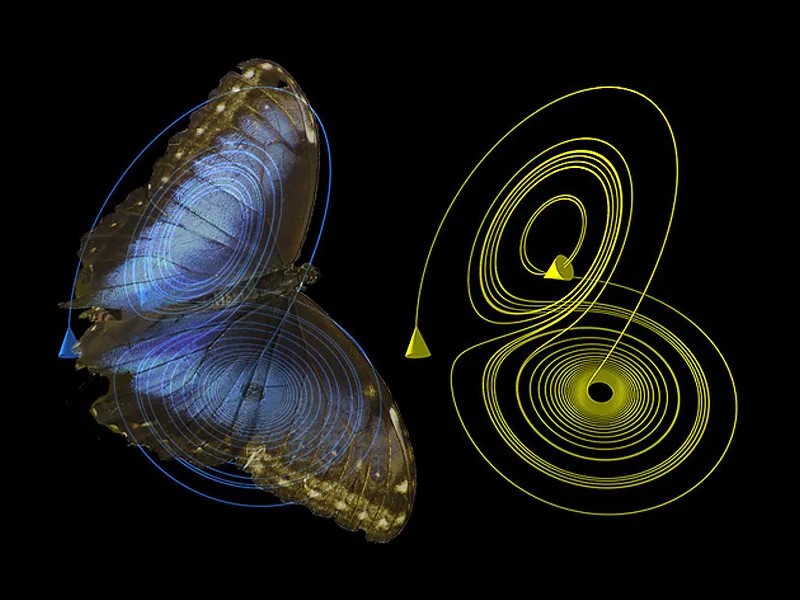

The Chain Reaction of Us

our story is made of chain reactions – we are just the sum of tiny miracles pretending to be[…]

FIGuring Life Out

Looking at Sylvia Plath’s Fig Tree: On Choice, Possibility, and Growing Into Who We Are I turned eighteen recently,[…]

The F-Word We’re Afraid To Say

WHY ARE WE SO SCARED OF THE WORD “FEMINIST”? There’s a strange, bitter irony in the fact that a[…]

No responses yet