While I was staying at my cousin’s house in Italy over the summer, I noticed a book on her nightstand that looked familiar. It was Powerless by Lauren Roberts- something I’d read when it first came out in English. But this one was the Italian edition, and out of curiosity, I started reading it one night before bed. I wasn’t expecting much of a difference beyond the language, but as I kept reading, it felt like an entirely different book. The characters didn’t just speak differently, they seemed different altogether. The way they looked in my head shifted. Their personalities felt slightly off, like I was watching the same people from a different angle. Even the setting came across differently. Nothing had been obviously changed, but the experience wasn’t the same at all; that’s when I started wondering how much of what we get from a story depends not just on the plot, but on the language we’re reading it in.

It’s not just about literal meaning. Translation reshapes tone, imagery, characterisation, atmosphere and It can completely alter the way a scene lands, or how a character feels in your mind. Reading in two languages doesn’t just give you two versions of the same story- I found it gives you two different stories entirely.

How Translation Changes More Than Just Words

Most people assume that a good translation is one that’s “faithful” to the original. But that’s not always possible. Languages aren’t one-to-one systems- they carry different rhythms, cultural nuances, and idioms that don’t transfer cleanly. Even sentence length can affect mood. English, for instance, often builds tension through short, clipped sentences. Italian tends to favour more lyrical, flowing phrasing. So when a writer creates urgency through terse prose, that urgency may dissolve in translation, even if the plot stays the same.

And then there’s style. Some translators lean more literal; others are more interpretive. I read an article on Jane Eyre translations (from English into Russian) which showed how Brontë’s descriptions of Jane’s appearance varied widely across six different versions. In some, she’s plain and cold. In others, she seems more assertive or even romantic. These aren’t small tweaks. They shape how the reader connects with Jane or whether they connect with her at all. (This was from a research piece in the journal Target; it’s pretty dense, but worth a skim if you’re into stylistics.)

This isn’t just a Russian-English thing. A study I came across on Yi Sang’s Korean short story Wings looked at how three different English translations handled the main character’s internal monologue. Even when the literal meaning stayed the same, the way verbs were structured shifted how passive or active the character felt. One version made him seem lost and weak and then another made him come across as quietly resisting the world around him. Just based on verb choice.

Readers Know When Something’s Off

I started digging into reader responses too. On a Reddit thread about fantasy translations, someone said that in some Italian editions of English fantasy novels, a “direwolf” had been translated as a “werewolf,” and a “stag” became a “unicorn.”- not just inaccurate, but thematically dissonant. Another reader pointed out that names and titles are often changed to sound more natural to local readers, which can make the story feel oddly less immersive. Even punctuation gets altered sometimes, which affects pacing and emphasis. It might seem small, but those changes matter because they shape how we emotionally engage with a scene.

Translators Are Co-Authors

There’s this idea that a translator is invisible- someone who simply transfers meaning like a courier. But in reality, they’re more like co-authors. They’re making creative decisions constantly: Should this be formal or casual? Do I preserve this cultural reference or replace it with something local? Do I keep the sentence structure awkward but faithful, or rewrite it so it flows better? Every choice tilts the story slightly.

I found a study (on arXiv, the open academic archive) comparing how human versus machine translations affected reader experience in Catalan. Not surprisingly, human translators scored way higher on creativity and emotional tone. The machine-translated versions felt flatter, even when they were technically accurate. That makes sense. Machines aren’t great with connotation, subtext, or pacing- at least not yet. Translators, by contrast, have to feel the story. They have to understand character motive, cultural tension, subplots- It’s not just about grammar.

The Risk of Losing the Original Voice

There’s always a tension in translation between fluency and fidelity. If a translation reads too smoothly, it can lose the quirks and rough edges of the original. If it sticks too closely to the source, it might feel awkward in the target language. Some translators argue for “domestication” -making the text feel native to the reader. Others prefer “foreignisation”- preserving the source language’s strangeness so that readers remember they’re reading a translation.

Both approaches have trade-offs. When I read Powerless in Italian, I felt like it had been domesticated a little too much. The fire of the original had been cooled down to fit Italian expectations of tone and drama. It wasn’t badly translated, just… gentler. The main character’s fierceness had a softness around the edges. It changed how I saw her and somehow changed the moral weight of her decisions.

Reading Between the Languages

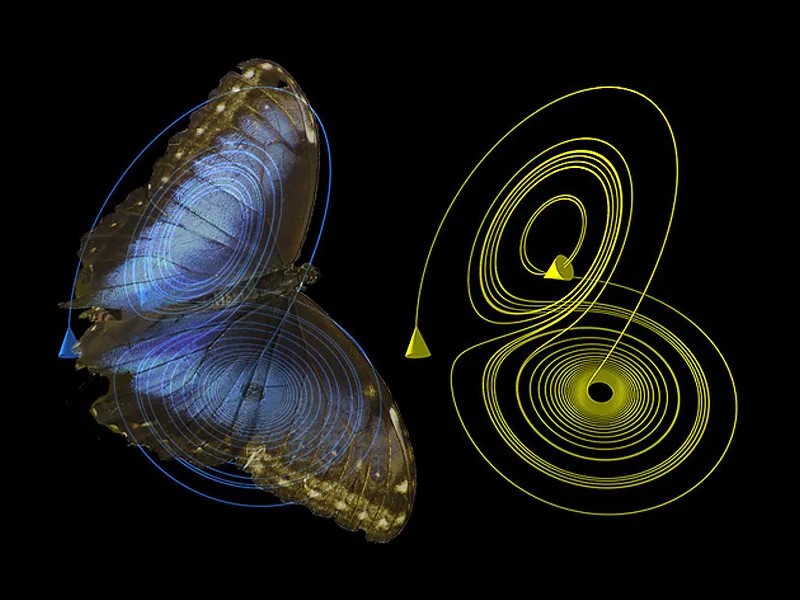

I don’t think there’s a perfect translation. But reading both versions of a book can open up a more layered experience. It’s like seeing two photographs of the same moment from slightly different angles. Sometimes it makes the moment clearer. Sometimes it highlights what one version is missing. For me, that difference wasn’t just interesting- it was a bit unsettling. It made me realise how fragile stories are. How easily they shift shape.

This matters even more for stories that deal with power, identity, resistance- anything emotionally charged. If the emotional register of a scene changes, the whole story’s message can tilt. In one translation of Wings, the main character’s moment of rebellion reads like a breakdown. In another, it feels like empowerment. That difference isn’t just academic as it highly affects how readers engage with the story’s ethics.

What This Means for Writers, Readers, and Critics

For writers, especially those hoping to be translated someday, it’s worth remembering that what you write is only part of the equation. What people read may be something different altogether. That’s not necessarily a bad thing but it’s a good reminder that books are alive in the reader’s language, not just the author’s.

For readers, it’s an invitation to be curious. Try reading your favourite book in translation, if you can. See what gets lost, what gets added, what stays strangely the same. Read translator notes, if they exist. Some translations even come with introductions that explain why certain choices were made. They’re fascinating in themselves.

And for critics, there’s a responsibility to remember that translation isn’t a neutral act. It shapes meaning. It can reinforce cultural assumptions or challenge them. It can elevate a book or flatten it. It’s a craft and like all crafts, it reflects the maker’s hand.

Final Thoughts

Reading Powerless in both English and Italian didn’t just teach me about translation. It taught me about perception and how the way we read is inseparable from the language we read in. When that language changes, the story does too. I used to think of translation as a kind of mirror, reflecting the original. But now I think it’s more like a prism: the story passes through, and what comes out the other side is familiar, but always coloured by the lens.

The Chain Reaction of Us

our story is made of chain reactions – we are just the sum of tiny miracles pretending to be[…]

FIGuring Life Out

Looking at Sylvia Plath’s Fig Tree: On Choice, Possibility, and Growing Into Who We Are I turned eighteen recently,[…]

The F-Word We’re Afraid To Say

WHY ARE WE SO SCARED OF THE WORD “FEMINIST”? There’s a strange, bitter irony in the fact that a[…]

No responses yet